James Augustine Healy: From slave to scholar to shepherd

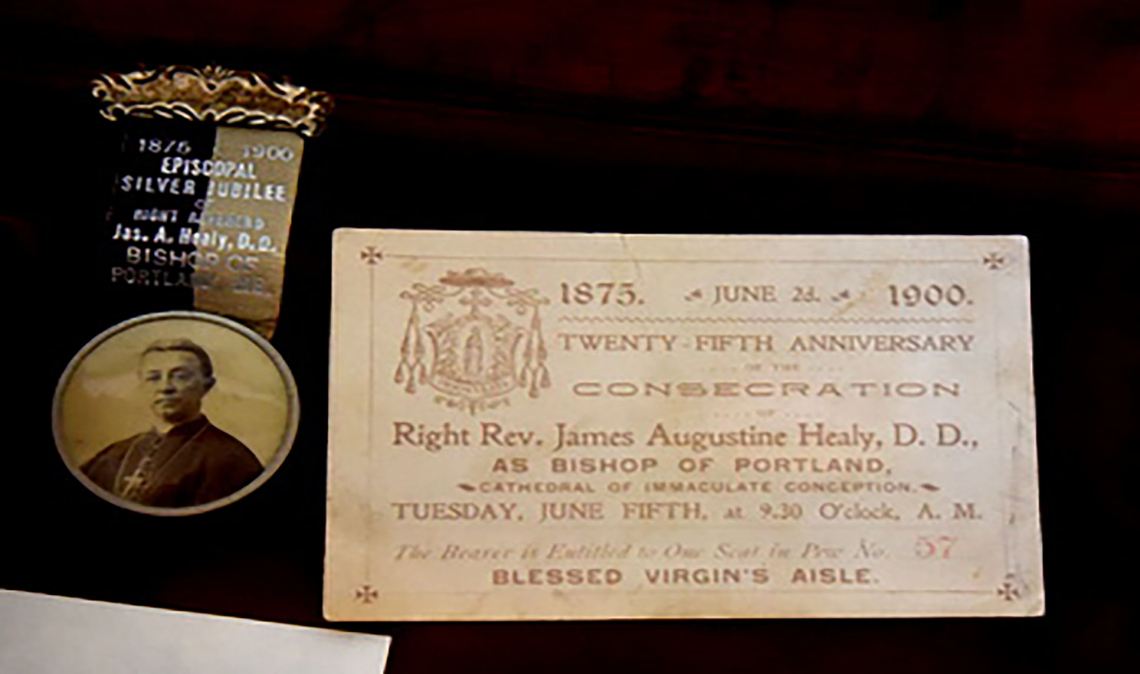

November 28, 2020, was a historic day for the Catholic Church in America. On that day, Archbishop Wilton Gregory of Washington, D.C., was created a cardinal by Pope Francis making him the first African American bishop to attain that rank. Cardinal Gregory’s selection by Pope Francis comes 145 years after the first cardinal from the United States was named, Bishop John McCloskey of New York. It was in that same year, 1875, that the country welcomed its first African American bishop, Bishop James Augustine Healy, the second bishop of the Diocese of Portland.

“It’s truly an American story, and it’s truly a Catholic story,” says Barbara Miles, archivist for the Diocese of Portland since 2017.

It’s also a story that has gained renewed interest in recent years.

“Since I’ve been in the diocesan archives, I’ve had at least six scholarly researchers come and look at the life of Healy,” says Miles. “I’ve got researchers standing in line, waiting to get in.”

James Healy was the son of Michael Morris Healy, a wealthy Georgia plantation owner originally from County Roscommon in Ireland, and Eliza, a slave, who was the daughter of a black woman and a white man. When Healy was 33 years old, he bought Eliza, then age 15, her mother, and six siblings, paying $3,700 for them.

“She was lighter skinned and Michael Morris Healy was attracted to her, and he was wealthy enough to buy the whole family,” says Miles. “He called her his wife, but they never married. It was illegal for a slave to marry a white man.”

Born in 1830, James was the first of Michael and Eliza Healy’s 10 children. Because their mother was a slave, the children were all considered slaves from birth, which barred them from attending school. Wanting to give his children an education, Michael Healy brought them north, beginning with James at age 7. The boy would never see his mother again.

“This is a story of absolute love. His mother had to love her children enough to give them away. She had to know that they would be free, even though she never would be,” says Miles. “Eliza lost all of her children to freedom.”

Michael Healy found a Quaker school in Long Island, N.Y., willing to accept James, and, later, his brothers Hugh and Patrick. James then continued his education at a Quaker school in New Jersey. Unfortunately, the brothers experienced discrimination because of both their African and their Irish heritage.

Michael Healy frequently traveled for business, and on one of those trips, he met Bishop John Fitzpatrick of Boston, a fellow Catholic and a fellow Irishman. It was an encounter that would change the course of James’s life.

“Bishop Fitzpatrick and Healy and the relationship between them is crucial to James Augustine Healy becoming the first African American Catholic bishop,” says Miles.

The bishop convinced Healy to transfer his sons to the newly built Jesuit College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Mass.

“Bishop Fitzpatrick accepted him into the school knowing he was black, knowing that he had not been baptized, and not knowing whether he was raised Catholic or not, because there was no Catholic church down in Jones County, Georgia, at the time,” says Miles.

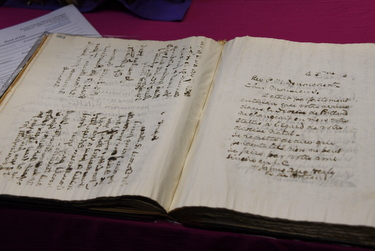

When it opened, Holy Cross was not strictly a post-secondary school. It had students ranging in age from seven to 31. James was 14 when he enrolled in 1844. The brothers, now including 8-year-old Alexander Sherwood, were baptized soon after arriving. James later wrote in his diary: “Then, I was nothing; now I am Catholic.”

The brothers all did well academically, especially James.

“He just absorbed knowledge uncannily,” says Miles.

Evidence of the Healy brothers’ academic abilities can be found in a collection of hand-cut, silver crosses that the college gave to them for scholastic achievement. The crosses, as well as some given to relatives, were recently gifted to the Diocese of Portland by descendants of the Healys.

“Our grandmother Bess was Bishop Healey’s niece. She had them,” says Tom Riley. “Some are from James. I think there might be Patrick, and there definitely is Hugh.”

James was named valedictorian of Holy Cross’s first graduating class in 1849. In his commencement address, he expressed appreciation for the welcome he found there, telling his fellow students that the college was “entwined with the memory of the brightest and happiest days of our existence.”

After graduation, James was accepted into the Sulpician Seminary in Montreal, Quebec. He continued to do well but mourned the deaths of both his mother and father while there. He also worried about his prospects for ordination because the needed documentation included his parents’ valid marriage certificate, which was unattainable. Again, Bishop Fitzpatrick stepped in and cleared the path. James was ordained to the subdiaconate, a minor order at the time, and then continued his studies at the Sulpician Seminary in Paris, France. He was ordained to the priesthood at the Cathedral of Notre Dame in 1854.

Father Healy returned to Boston, Mass., unsure how he would fit in, his concerns expressed in a diary entry in which he refers to himself as a “poor outcast.” It was a time of discrimination against Catholics, against Irish immigrants, and against African Americans. Although he was light-skinned like his mother, Father Healy’s heritage was known.

“He never proclaimed his racial identity. He was very quiet. He didn’t deny being an African American, but he didn’t publicize it either,” says Miles.

Bishop Fitzpatrick continued to be a great advocate, assigning Father Healy to the House of the Guardian Angel, which took in homeless boys. His care and concern for children would become hallmarks of both his priesthood and his episcopate.

"Maybe it's because he was taken away from his mother when he was a child that his heart was dedicated to orphans and to destitute children who were removed from their parents. There is a huge volume of work that he did with homes for destitute children in Boston and later in Maine,” says Miles.

Bishop Fitzpatrick then chose Father Healy to be his personal secretary. Positions as chancellor and rector of the cathedral would follow. After Bishop Fitzpatrick’s death in 1866, the new bishop assigned Father Healy to be pastor of St. James Parish, the largest parish in Boston. He ministered there until 1875, when, just 10 years after the end of the Civil War, Pope Pius IX appointed Father Healy to succeed Bishop David Bacon as Bishop of Portland.

“By the time his appointment as Bishop of Portland came, he was ready. His education, his pastoral and administrative experience, his natural love for children and minorities, as well as his noted charm prepared him to serve and to serve as a good shepherd,” Bishop Joseph Gerry, OSB, the 10th Bishop of Portland, commented in August 2000, during an observance marking the centennial of Bishop Healy’s death.

“When he came to Maine, he continued his responsibilities as a leader, as a fine administrator, and as a statesman,” says Miles.

Bishop Healy notes in his diary that he found everything in good order upon his arrival. “The bishop elect finds the episcopal residence very good and the Cathedral church and chapel very fine and well-appointed in all things,” he wrote.

Bishop Healy had some familiarity with Maine, having spent time with the Kavanaugh family in the Damariscotta area, where there was an Irish Catholic community, but he soon set off to discover more of the vast diocese, which then included both Maine and New Hampshire. His diaries tell of continual trips covering thousands of miles by steamboat, canoe, train, and on horseback. He often expressed appreciation for the people he met. In July 1875, after traveling to Bangor, the bishop wrote that he was “much pleased with his visit and much surprised at the beauty and wealth of Bangor.” Following a trip to Trescott later that month, he described having met “very excellent and simple, though intelligent people.”

Despite the prejudices still prevalent at that time, Bishop Healy never distanced himself from the people, and he came to be beloved.

“Those he served ended up taking him to their hearts not because he was black or white but because of his living faith,” Bishop Joseph said during the centennial observance. “What enabled him to serve so faithfully was his love for Christ, his ability to listen to Him and to follow Him, his desire that others come to know the same Christ he knew.

During Bishop Healy’s 25 years as bishop, the Catholic population of the diocese more than doubled, due to an influx of Irish and French-Canadian immigrants. His own Irish heritage and his ability to speak French proved to be assets as he sought to serve them. To meet their needs, 60 new churches, 68 missions, and 18 schools were built, many in rural communities. Bishop Healy also welcomed many religious communities to the diocese, most of them French-speaking, to serve the newly arrived Catholics, and in 1884, he oversaw the establishment of the Diocese of Manchester.

Bishop Healey battled health issues during the last years of his life and died in August 1900, just months after celebrating his 25th jubilee as bishop. It was his wish not to be buried in the crypt of the cathedral, as had been his predecessor, but in a simple coffin in Calvary Cemetery in South Portland. It was reported that hundreds who attended the funeral Mass at the cathedral walked to the cemetery about five miles away for his burial. A Celtic cross now marks his grave.

Bishop Healey wasn’t the only member of his family to leave a lasting legacy. His brother Alexander Sherwood also became a respected priest and rector of the cathedral in Boston. Patrick became a Jesuit priest and the president of Georgetown University and has been referred to as its “second founder” for transforming it into a world class university. Two sisters joined religious orders, one becoming a mother superior. And younger brother Michael joined the Revenue Cutter Service, a forerunner to the Coast Guard, spending 20 years patrolling the Alaska territory. Known for his care of the native people, he was the third highest ranking officer in the service at the time of his retirement. A Coast Guard icebreaker is now named in his honor.

Sources:

Diocese of Portland’s Archives; The Church World; The Catholic Church in the Land of the Holy Cross by Vincent A. Lapomarda, SJ; Bishop Healy: Beloved Outcaste by Albert S. Foley, SJ; and the U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office website.