"This is where the Lord Wants me."

Father Steven Cartwright says it’s hard to put into words what he was experiencing when Bishop Robert Deeley laid hands on him and prayed the prayer of ordination, asking God to grant to "this, your servant, the dignity of the priesthood.”

“There is so much I was feeling: so much gratitude, so much love,” he says.

He describes himself as being incredibly at peace.

“This is where the Lord wants me. He has made that abundantly clear,” he says.

Cartwright was ordained a priest of the Diocese of Portland by Bishop Deeley on Saturday, June 13, at the Cathedral of the Immaculate in Portland.

“God has led you here. He has created you for this moment. Your ordination is the culmination of several years of careful discernment, some side trips when, one might say, you were swimming outside the priestly lane, much fervent prayer and hard work, and, of course, the generous outpouring of God’s grace,” the bishop said. “May your ministry in the name of Jesus be a ministry of joy and mercy for each of those entrusted to your care.”

During the ordination Mass, Deacon Cartwright affirmed his willingness to become a priest, promising respect and obedience to the bishop and his successors. He then lay prostrate while the Litany of Saints was sung.

“During the litany, hearing all the saints and their names called out, it was surreal, absolutely surreal,” he says.

|

|

The most solemn part of the rite follows the Litany of Saints. The bishop laid hands on Deacon Cartwright in silence, and the more than 30 priests present then did the same. Bishop Deeley then prayed the consecratory prayer, asking the Lord to help Cartwright to “be a worthy co-worker with our order, so that, by his preaching and through the grace of the Holy Spirit, the words of the Gospel may bear fruit in human hearts."

Now ordained, Father Cartwright was vested with the stole and chasuble, symbols of the priesthood, by Father Timothy Nadeau, pastor of Saint Paul the Apostle Parish, Bangor, and Father Louis Phillips, pastor of Our Lady of Perpetual Help, Windham; Saint Anne, Gorham; and Saint Anthony of Padua, Westbrook.

Once vested, Father Cartwright’s hands were anointed by the bishop who then presented him with a chalice and paten, telling him: “Imitate the mystery you celebrate: model your life on the mystery of the Lord’s cross.”

The bishop and Father Cartwright’s brother priests each then welcomed him to the presbyterate with the fraternal kiss of peace.

|

|

|

|

Father Cartwright’s first assignment will be at Prince of Peace Parish, Lewiston, and while he’s looking forward to it, he says he would have been happy wherever he was placed.

“It’s incredibly humbling to be back home, to be in Maine, to be able to serve,” he says. “I know God loves me very much, and to be able to share that love, to tell others about that burning love for them, I can’t imagine doing anything else.”

While that is now the case, Father Cartwright’s path to the priesthood was anything but direct.

“You always see God a lot clearer in the rearview mirror than you do in the windshield,” he says.

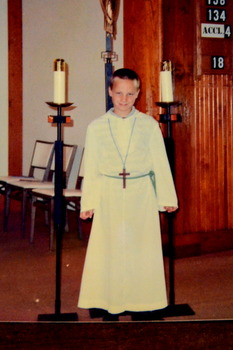

Father Cartwright says he first felt called to be a priest when he was growing up in Boothbay Harbor. He began altar serving around the age of nine, not long after making his first Communion. He recalls the excitement he felt the first time he was going to serve. It was going to be a surprise Father’s Day gift for his dad, but unfortunately, he gave away the secret while chatting on the phone.

“I’m talking to Uncle Norman saying, ‘Guess what, Uncle Norman? This weekend is Father’s Day, and I’m serving Mass for the first time!’ And Dad was sitting right across the counter. I was so excited that I just blurted it out. I was devastated,” he recalls.

Father Cartwright’s parents were both active in the church, and on that day, his dad was going to be reading at Mass, and his mom was going to be playing the organ.

Throughout his childhood, faith was always part of Father Cartwright’s life. He remembers ‘playing Mass’ at a friend’s house after attending Sunday Mass, and then starting to do the same at home. He says his mother would buy NECCO Wafers, and he would take all the white ones out to use as hosts.

“I remember asking Mom, ‘Do you have that flat thing that the priest uses to put the bread on?’ And she says, ‘That flat thing that the priest uses? Are you talking about a paten?’ I said, ‘Yes, a paten. Do you have one?’ She says, ‘No, I don’t have one. Why would I have one?’ I wanted it to start playing Mass. Well, over the years, it kind of grew substantially.”

Father Cartwright says the second floor of their house was unfinished, and he converted it into a church. A friend of his mother’s had a reredos from the high altar of the original church and gave it to him. His mother helped create a paschal candle for him, using a wrapping paper tube topped off with a votive candle. She also made him altar cloths and coverings for his lectern.

“I had each liturgical color, and she also made some vestments. I still have them,” he says.

He also still has a chasuble that was given to him by Father Marcel Chouinard, then pastor of Our Lady Queen of Peace Parish in Boothbay Harbor. Father Cartwright had the decorative orphery removed from it and stitched onto a new chasuble, which he used for vesting.

“He was the first priest who ever nourished my vocation,” Father Cartwright says. “He would be my bishop, and when he would come over to the house for family gatherings, he would have to inspect the church.”

“My dad was a great man. Even though my dad, of course, wasn’t a priest, he was a priest of the domestic church. He taught me how to be a father. Not only do we need good husbands and fathers, we need priests who are good fathers,” he says.

Father Cartwright believes it’s providential that his diaconate ordination took place on Father’s Day and his priestly ordination on what would have been his dad’s 76th birthday.

“There are no coincidences in the spiritual life. I only hope I can be as good a priest as my dad was a father to me,” he says.

Despite the strong call to the priesthood he felt as a child, Father Cartwright had another love, swimming. He started swimming at age four, and at age 15, he left his home in Boothbay Harbor for Bangor, so he could join a respected swim club there. He was seeking advanced training in hopes of swimming his way to a college scholarship. It worked out as hoped. He attended Saint John’s University in Queens, New York, for a year, before transferring to Saint Bonaventure University, also in New York.

With the priesthood still in mind, he majored in philosophy, and after two years, he met with then vocations director Father Daniel Greenleaf and was accepted as a seminarian into the Basselin Scholars Program, an honors philosophy program at Theological College, the national seminary of Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.

He earned his bachelor’s degree but also came to the conclusion that the priesthood wasn’t for him after all. He left formation, a decision he says that he has never regretted.

“Obviously, there was some disappointment, but it wasn’t time,” he says. “Certainly, it wasn’t in the Lord’s time.”

“It was absolutely wonderful,” he says.

A year and a half later, it got even better when he was promoted to head coach.

“The only thing that I’ve ever wanted to do, other than being a priest, is to be a Division 1 head coach,” he says. “I had my dream job. I had everything I wanted.”

During these years, Father Cartwright says he not only pushed aside the priesthood but also his faith.

“I never stopped believing. I just didn’t feel the need to practice my faith. I wanted to do my own thing and go my own way.”

He says, however, his mother never stop praying for him.

“Mom always sends cards. Any occasion for a card, Mom will send me a card. If there was a card for it, it got in the mail just to let me know she was thinking about me. And there would always be a little note like, ‘He’s still there,’ or ‘He’s watching out for you.’”

His mother also tucked religious publications or reflections into the cards, which he admits always ended up in the trash.

“I didn’t care. I didn’t have a need. I didn’t have a hunger,” he says.

He remembers driving home from the university around Christmastime and feeling the urge to go to a church. He stopped at one that was along the route he traveled.

“Something urged me just to go, just to be there, and I remember pulling into the parking lot. There wasn’t a car there. I remember it was raining, and I went to the door of the church, and it was locked. I was so upset. I just sat in my car, and I just cried. It was uncontrollable.”

He says he came to realize that something was missing from his life.

“I was empty, just absolutely empty.”

It led him to begin attending Mass again, and for the first time in years, he went to confession. He calls it a huge turning point.

“I literally went in with pages. I had to write it out,” he says. “I’ll never forget that day. I still remember where I was. I still remember the moment. I still remember everything. And I just remember crying. I had come back home. My sins had been forgiven. And to receive the Eucharist again, to come back home, what a gift that was for someone so undeserving.”

He finds the sacrament of reconciliation so powerful that he says hearing confessions is what he is most looking forward to now that he is a priest.

“You’ve been given more grace to live your Christian life stronger,” he says. “We’re all falling down and continually getting up in our lives. We have to. It’s who we are. But the sacraments of confession, reconciliation, what a gift to the entire world.”

He says reconnecting with his faith meant making some needed changes to his life. And although it didn’t happen immediately, he again began to feel the pull of the priesthood.

Different because he had more to lose. Returning to the seminary would mean giving up his career.

“There was a huge element of sacrifice that wasn’t there before,” he says. “Initially, I just totally threw the thought out of my mind. I’ve done this before. I’m not going back. You’ve got to be kidding me. We were already here. We were here 15 years ago. You want me to go back?”

But, he says, the Lord was persistent.

“The Lord, in His goodness, never left me.”

He resumed formation in 2010, first opting for the Diocese of Raleigh, North Carolina, because he knew priests there and because it was close to Washington, D.C. Two years later, he transferred to the Diocese of Portland, attending Pope Saint John XXIII Seminary in Weston, Massachusetts.

At age 31, he says he entered seminary with a more mature perspective.

“What I held on to this time is that you go to seminary really to fall in love. Your relationship with the Lord is of primary importance, spending time with the Lord every day, being with Him, spending time in prayer, even if you have nothing to say. And through that relationship, over the years of being in seminary, staying faithful to that, the Lord’s will will become revealed, not in lightning strikes, or voices, or claps of thunder or anything like that, but there is a peace that comes. There is a tranquility that comes,” he says. “Vocation is realized and spoken to in silence, a lot of time in prayer and discerning what the Lord wants for your life. You pray for the grace to cooperate with it.”

He says he looks at his ordination day not as the culmination of a journey but as the beginning of one.

He says he looks at his ordination day not as the culmination of a journey but as the beginning of one.

“You go through all these years of preparations and assignments and classes and supervisors and reports and evaluations, these seven or eight years, and still, the day you wake up after your ordination day is the first day of your life that you’ve ever lived as a priest.”

He says when he awoke the next morning, it was with “a sense of overwhelming gratitude to God, to His gift of His Son, and to be given the gift of sharing in His priesthood.”

He describes it as very humbling.

“Very peaceful, very joyous,” he says. “What a beautiful gift it is waking up as a priest.”