A revival of hope for struggling students

For more than 25 years, St. Mary’s Renaissance School has been helping children who have struggled to fit in and succeed in public school classrooms. Part of St. Mary’s Health System, the Auburn school serves children from grades one through eight who have behavioral issues.

“We serve students who are unable to behave safely in their current public school district for whatever reason. They are referred to us, and we provide treatment and education to help them develop skills and learn to be safer in those public districts,” explains Stuart Beddie, the director.

The students at St. Mary’s Renaissance School all have mental health diagnoses, but the reasons behind them vary greatly.

“It can be for a wide range of issues, whether it’s developmental or socioemotional. We have a lot of trauma, a lot of poverty, a lot of disrupted families and placements,” says Beddie. “We take pretty complicated cases where typically it’s not just one issue. So, we’ll have some kids on the autism spectrum who also have trauma and poverty and those kinds of things.

"Unlike a traditional school setting where the focus is on education, the Renaissance School combines teaching with clinical treatment.

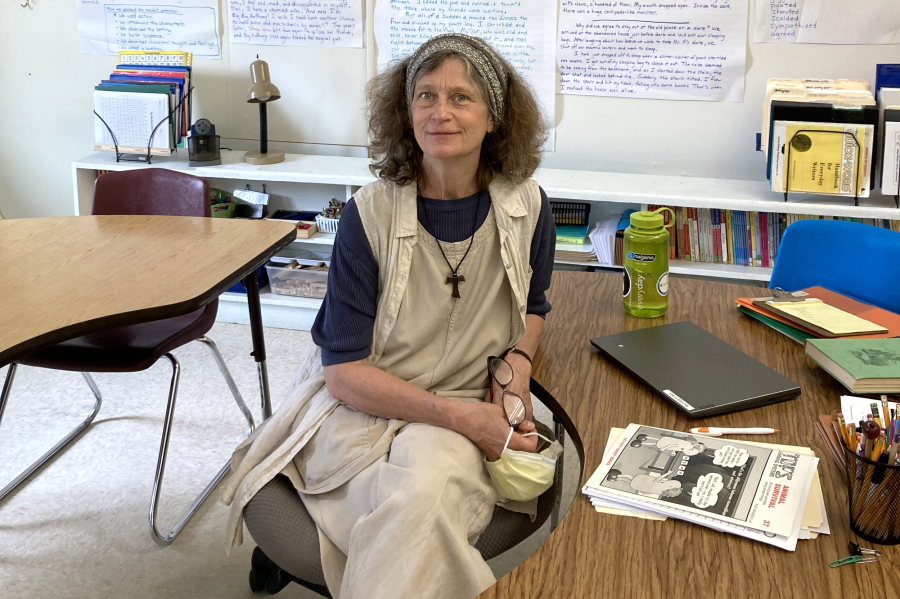

“The students have related services, counseling services. They have social work services. Some also have speech services or occupational therapy sessions,” says Margaret Templeton, a special education teacher.

While they receive individualized treatment, the students are taught in small classroom settings of six to eight students.

“We do pull-out services for kids who have weak areas to bring them up, but we’re also really focusing the whole time on how to function in a small group safely, because a small group is where they will be in their local districts if they’re able to successfully go back,” says Beddie.

It is a highly structured and supervised environment. Along with a special education teacher, each classroom also has behavioral health professionals/ed techs (BHPs), putting the student-adult ratio at two to one.

“Why this program is effective is because there is a level of contact with the adults in the program, with the direct care staff, with the social work staff, with the teaching staff. There is that level of relationship so that the program can address, for that individual child, what is going on for them,” says Templeton.

“We’re all geared toward meeting the needs of the children,” says Corey Gagnier, the lead BHP. “Everyone is part of the team. Not a single person isn’t engaging with the kids.”

Gagnier and Templeton stress the importance of providing positive adult role models and forming supportive relationships with the students.

“I kind of abide by the three r’s, which are rules without relationship equals rebellion,” Gagnier says. “It’s about joining them where they are at, providing rewards for things that they do well or things that we ask them to do, and being firm but friendly.”

“So much of what builds resilience in the world as we’re developing is about relationship,” Templeton says. “While they are still young, children really do want that positive interaction with adults in their life, and if we can provide that, then that can be that little turning point that just adjusts things and veers them into a new direction.”

Templeton says because the children are in a safe, supportive environment, a sense of trust builds not only with the adults but, also, with their peers.

“In my classroom, we have a culture that is extremely supportive. The kids have built such a solid team. They help each other. They encourage each other. If somebody is going through a difficult time, they give them space,” she says.

Templeton, who teaches sixth, seventh, and eighth graders, says each day in her classroom begins with a group work session, followed by stretching to get the kids moving, then a writing workshop, which the kids love. She follows that up with group reading sessions and individualized math sessions and then social studies and science. The arts are included on Fridays. Students can also earn time for a preferred, end-of-the-day activity.

Templeton says she uses a lot of hands-on work and projects to keep the students interested and involved.

“We try to keep everyone at a good challenge level without straying into their frustration level,” she says. “It’s important for the kids to stay engaged and feel successful.”

And success does happen.

“I think these kids have so many gains they can show. It’s really exciting to give them the opportunity, to see the resiliency they can exhibit if just given those supports,” says Templeton. “I see the progress day to day, not just the ones who are under my care but in all the rooms.”

“It can be challenging, but the rewards that we get are when kids successfully transition out of here,” says Gagnier.

“These kids earn their way in, and they earn their way out.”

St. Mary’s Renaissance School has a high rate of returning students to public school, and while Beddie says it’s difficult for them to track what happens from there, some students do come back to share how they are doing.

“We’re pretty happy because there are a relatively large number of kids who do that,” he says.

The Renaissance School has been helping students since 1996. That is when it was founded by two psychiatrists, Dr. Eric Griffey and Dr. Luis Velazquez. Dr. Valezquez had worked in a similar setting in New York and saw a similar need here in Maine.

While a school such as this may seem like an outlier for a health system, Beddie says their work goes back to St. Mary’s founding mission.

“If you take it all the way back to St. Marguerite d'Youville and the sisters in Montreal, it’s about working with children and struggling families around a variety of issues: poverty, abuse, neglect, anything else that might be going on,” he says. “We really are a replication of those early services provided by the nuns.”