A Positive Prognosis

Thanks to the Assistance of Catholic Charities Maine

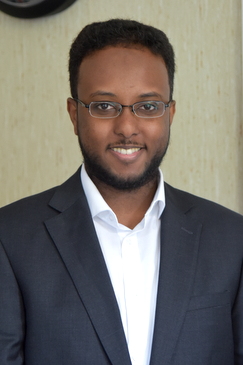

Hoping to follow in his father’s footsteps and practice medicine, Dr. Hassan Mahmoud began his residency at Maine Medical Center in Portland in July. It is something he has worked towards since entering college 10 years ago.

“It means that this long journey ended up with a happy ending,” he says.

The ending may have been different, however, if Dr. Hassan had not received the assistance of Catholic Charities Maine.

“Their support and their services were very helpful,” he says.

Dr. Hassan and his family arrived in this country from Syria in 2013 through the United States Refugee Resettlement Program. His family is originally from Somalia, although he grew up in Saudi Arabia, where his father worked. When his father’s residency permit was not renewed after 15 years, the family needed to relocate. Because of the unrest in Somalia, they chose Syria, and Hassan began his studies at the University of Aleppo Faculty of Medicine.

His family knew, however, their stay there would only be temporary.

“Syria was not my country. I was a refugee. My whole time there, we tried resettlement through the U.N. program of resettlement,” he says. “The main reason is because I was not there as a permanent resident. I was just there for school, and when I finished school, I had to go somewhere else.”

While the family could not choose the country to which they would be relocated, he says they were pleased to learn it would be the United States.

“We were happy, and we were excited about moving to the U.S.,” he says. “I knew the United States is a stable country. It’s safe. It’s not like the place we used to live, when the unrest in Syria started. Also, I had my own dreams about getting residency and completing medical training here.”

While refugees cannot choose a specific country, once accepted into the U.S., they can request a state if they have connections there. Dr. Hassan’s family chose Maine because they have extended family here.

When Dr. Hassan and his family arrived in Portland, they were greeted at the Jetport by representatives of Catholic Charities Maine’s Refugee and Immigration Services program (RIS). While it is the U.S. State Department that accepts refugees into this country, after they are given refugee status by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the State Department contracts with agencies such as Catholic Charities Maine to help refugees get established once here. That includes finding them a place to live, connecting them with services, working on language skills, enrolling children in schools, and helping adults find jobs.

“We do employment assessments. We do employment orientation. We help people with writing resumes and doing short- and long-term employability plans,” explains Tarlan Ahmadov, RIS program director. “We coach them for the interviews, and we follow up with them afterwards, if they are placed in jobs.”

“I think because of the effect of my father, seeing him help people,” he says. “And even in school, I was interested in science and biology.”

While his degree was from an accredited university, foreign medical graduates face some hurdles. Dr. Hassan says they must pass a series of three tests, the first of which costs $1,000, a daunting amount for a newly arrived family.

“I was not working. I did not have any savings to pay for that, but they helped me through that,” he says. “They actually paid for my first exam’s fees, which is not cheap at all.”

Because Catholic Charities stepped in, Dr. Hassan was able to begin studying immediately and was able to take the first test within the first six months. He says that is important because the more time passes, the less likely it is that hospitals here will want to accept foreign graduates into residency programs.

“You don’t have the luxury of saying, ‘O.k., I’ll come back to these tests a year from now.’ There are people who are refugees or immigrants who came to this country who couldn’t do the tests right away because they had families or something like that. They needed to go to work or do other things other than the exams. When they are out of this timeframe, there is nothing they can do,” he says.

Dr. Hassan says he was pleased to pass the first test, a written exam, on the first try.

“There are a lot of foreign medical graduates who take the test and fail the first time, and that will affect their application later on, but I’m glad I passed on my first attempt. So that was part one in six months, and then another six months, I took step two.”

Step two includes a written test and a simulated diagnosis, in which you examine what is known as a standardized patient, a person trained to act as someone who is ill.

“You go to a patient, take a medical history, do a physical exam, and then come up with a treatment plan,” he says.

He says there are only a handful of centers in the United States that offer the standardized patient tests, and he was fortunate to get a spot in the one in Atlanta.

“I was quite stressed about the last one because it has a lot of components that test you, not only the medical side. They test your communications skills, your language skills. So, I was quite afraid of someone not understanding my accent or something like that, but it went smoothly.”

By this point, he had begun working as a Somali – Arabic – English interpreter to earn income, and he and his family were able to pay for the second set of tests themselves.

“I was blessed in having such a family who were very supportive. They supported me with everything that I needed, until I finished these tests.”

While he was preparing for the exams, Catholic Charities also supported Dr. Hassan by pairing him with a retired doctor through a mentoring program. The doctor served at MaineGeneral Hospital in Augusta one day a week and let Dr. Hassan job shadow him.

“It’s not just doing these tests. You also have to have American clinical experience, where you shadowed an American physician and got recommendations from them, so that doctor helping me. I also shadowed at Portland Community Health Center.”

The third test will come during residency. Dr. Hassan applied to several hospitals last fall, and Maine Medical Center (MMC) was one of two that granted him an interview. He says after a four-week clinical rotation, during which the hospital got to see his work, and he got familiar with the hospital, he was accepted into MMC’s residency program.

“It means a lot,” he says. “My family, when I got this point, they were very happy and proud of me.”

He describes his father, who knows that his own medical career is over because he would not be able to tackle the rigors of residency, as being “very proud.” His father now works for the Maine Access Immigrant Network.

If all goes well and Dr. Hassan completes his residency and gets his license to practice, he intends to do a fellowship in a specific area of internal medicine. Although he’s not sure yet what his specialty will be, he says he has one goal in mind.

“I just want to help the people and do good for everyone.”