A gift of faith from a WWII foxhole

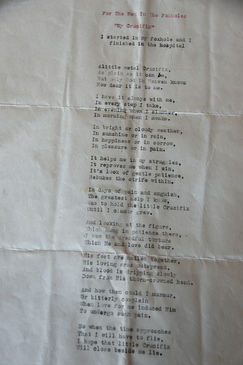

So begins a poem penned by a soldier more than 75 years ago, a sign of the faith he carried with him from the neighborhoods of Lewiston to the battlefields of WWII.

“I have it always with me, in every step I take, at evening when I slumber, at morning when I awake,” the poem continues.

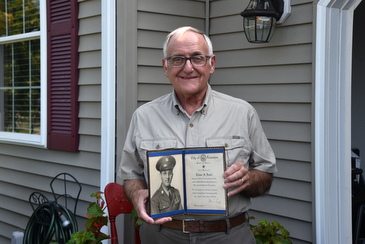

Entitled “The Crucifix,” the poem was written by Private First Class Elisée Dutil on the beachhead of Anzio-Nettuno, Italy, in 1944. It is one of many treasures preserved by his nephew Deacon Denis Mailhot, who serves at Immaculate Heart of Mary Parish in Auburn.

“I decided to take on this project because, for years, my mother, and my aunts on the Mailhot side, had meticulously kept all these pictures and postcards and photos,and newspaper clippings,” he says. “Once I saw all this, I said, ‘I have to put it together. I have to do this right.’”

Deacon Mailhot began organizing the collection in 2019, but when the coronavirus struck, it gave him the time he needed to immerse himself in the project. The result was two large binders full of mementoes and messages capturing his family’s history of military service from a great uncle who served in WWI, to uncles who served in WWII, to his own service in the U.S. Navy during the Vietnam War.

The photos and postcards, many written in cursive French, paint a picture of service, sacrifice, and faith. In a postcard to his parents shortly before he shipped overseas in January 1943, Elisée writes, “God, he had hardship, so why do we think we would not have a little hardship [too]?”

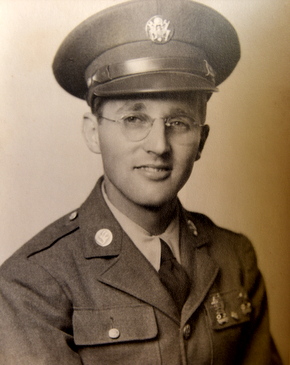

Elisée was sworn into the U.S. Army on June 9, 1942, at age 22. Born November 24, 1919, he attended St. Peter School in Lewiston and then Lewiston High School. He was active at Ss. Peter & Paul Parish (now part of Prince of Peace Parish), singing in the choir and with a male chorale society. He also belonged to two fraternal organizations: the Société des Défenseurs du Saint Nom de Jésus (Society for the Defenders of the Holy Name of Jesus) and the Cadets of the Catholic Order of Foresters.

“He was involved in his faith. He never missed Mass ever. If there was a chaplain doing a Mass during the war, he was there, I’m sure,” says Deacon Mailhot.

Elisée was a member of the 7th Infantry Regiment of the 3rd Infantry Division, one of the few divisions to fight in North Africa, Sicily, Italy, France, and Germany during the war.

During the invasion of Sicily, Elisée was injured in the leg, receiving the Purple Heart. He then fought at Anzio-Nettuno, a battle critical in the liberation of Rome. It was there, in a foxhole, that he began writing “The Crucifix.” Elisée dedicated the poem to his brothers in arms, urging them to also keep Christ close to their hearts.

“Elisée writes ‘The Crucifix,’ gives it to his men, so they will keep their Catholic faith, their Christian faith, strong in the worst situation that any human being could ever be put in,” says Deacon Mailhot. “There is no selfishness in that. He’s trying to evangelize his men, the men in the foxholes in 1944. He is writing this dedication, hoping they’ll remember their faith. He was concerned that if something happened to them, that they would go to heaven.”

It was at Anzio-Nettuno that Elisée was wounded again, this time more seriously. He was evacuated to a hospital in North Africa where, his faith unshaken, he completed the poem. A faded, typed copy states: “I started in my foxhole and I finished in the hospital.”

“These pages are what he typed on a typewriter during the war,” Deacon Mailhot says, pointing to pages in the binder. “It is my hope and prayer that copies of Elisée’s prayer found their way into the hands of all the soldiers ‘in the foxholes’ he served with, especially those who passed away into the loving and eternal embrace of God.

“He paid a great price that we as a free people might continue to enjoy all those things that make life worth living. By that, he showed his intense love for us: ‘Greater love than this no man hath, that a man lay down his life for his friends.’ Not only our nation but our very civilization is deeply indebted to him,” Lt. Col. Ralph J. Smith, a division chaplain, wrote to Elisée’s father.

“These guys were the greatest generation. The only reason, I believe, that the United States of America is still here today is that generation,” says Deacon Mailhot. “They sacrificed their lives.”

Just weeks before his own death, Elisée received word that his mother had passed away. Deacon Mailhot says the family often said she had come to get her son to end his suffering.

Originally buried in a cemetery in France, Elisée’s father paid to have his body returned home. He is now buried in the family plot at St. Peter’s Cemetery in Lewiston. It is not known whether his crucifix lies with him.

Although Elisée died before Deacon Mailhot was born, he says his uncle’s faith and poem were inspirations to him as he discerned his vocation to the permanent diaconate.

“Elisée truly imitated Christ throughout much of his too brief life,” he says.

Elisée’s poem also inspired others beyond the battlefields. Father Mitchell Koprowski, a chaplain who told Deacon Mailhot he was with Elisée at Anzio when he wrote the poem, later shared it with Carmelite Nuns in North Dakota.

“The sisters thought it was so wonderful that they took that prayer and made a prayer card. They distributed that in the religious order for decades,” says Deacon Mailhot.

.jpg) As we mark the 75th anniversary of the end of WWII, Deacon Mailhot says he hopes Elisée’s story leads readers to reflect upon the sacrifices made by so many, who put others before themselves.

As we mark the 75th anniversary of the end of WWII, Deacon Mailhot says he hopes Elisée’s story leads readers to reflect upon the sacrifices made by so many, who put others before themselves.

“It was my hope that PFC Eliseé A. Dutil’s prayer serves to inspire all of us that we are never alone, even during the COVID-19 pandemic, so that we may unite as one community, one state, and one nation under God,” he says.

Deacon Mailhot says the Franco-American Collection at the University of Southern Maine plans to digitize and preserve the material he put together. He expressed gratitude to Doris Belisle-Bonneau, a board member of the collection, and to students in Seth Goodwin’s French class at Edward Little High School in Auburn for helping to translate some of the articles and postcards from French into English.

Read "The Crucifix" and the Dedication.